These devoted women, known as Maenads, willingly cast aside familial ties and social standings to join him, surrendering to the primal essence the ancient Greeks believed all women inherently possessed. Armed with thyrsi, formidable fennel staves, these women reveled in intoxication, asserted their sexuality, and, when sufficiently provoked, displayed a penchant for tearing apart and consuming anything in their path, from lions to their own progeny. Failing to honor him with due worship and respect could invite his presence to your town—potentially luring women away as Maenads or, in the extreme, unleashing them upon unsuspecting men.

A maenad

Dionysus emerges as a later addition to the pantheon, and the myths surrounding him bear the traces of this tardiness. Both the Greeks of antiquity and contemporary scholars grapple with divergent theories regarding his origin and the emergence of his cult. While various accounts exist, the prevailing narrative suggests his migration to Greece from central Asia. The illegitimate offspring of Zeus, his potential mothers span from the mortal princess Semele to Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld. However, a common thread unites all these origin stories—Dionysus or his pregnant mother facing death, only for him to regenerate or complete gestation within the body of another parent.

This profound rebirth and transformation elevated him to significance within the enigmatic cults, clandestine religious movements centered on the concept of an existence beyond death (originally, Christianity was perceived as one such cult, serving as its primary rival until it was eventually suppressed by the Christianized Roman Empire). The rituals of these cults hinged on spiritual ecstasy, the attainment of an altered state of consciousness through transcendent experiences, often affording elevated status to women and other marginalized individuals compared to the societal norms. Within these cults, Dionysus is typically portrayed as the underworld’s Dionysus, the offspring of Zeus and either Persephone, the daughter of Zeus, or Demeter, the goddess of the earth. Referred to as Zagreus, his infancy is marked by a gruesome death, as he is dismembered by Hera’s servants only to regenerate through the implantation of his heart either in Zeus’ thigh or Princess Semele’s womb. In this narrative, Dionysus extends solace to his disenfranchised followers—women, the impoverished, and social outcasts—providing them respite from their afflictions through pleasure and the promise of a more favorable afterlife, irrespective of their social standing.

.

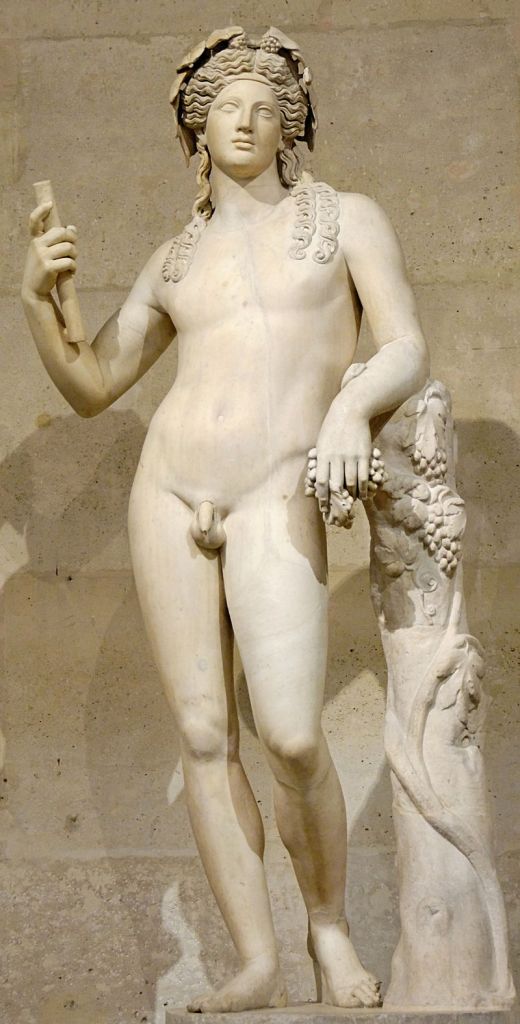

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5

His femininity, attached to a body defined as male, is a large part of what made him threatening. Despite ancient Greek women needing to live lives of exemplary sexual self control if they wanted to survive while ancient Greek men happily engaged in orgies and wrote about rape as if it were a casual sport, sexual self control was considered a purely masculine virtue. Intense desire and the inability to control it were the afflictions of women, or particularly effeminate men.

The fact that he sought out women and offered them wine, something their access to was heavily restricted due to the belief that it would make them lose what self control they had, made Dionysus a threat to the fundamental building block of the city state — that a man have legitimate children to replace him. We can still see this fear today in the cis male anxiety around queer and female sexuality, so afraid of losing their sexual dominion over women that they attempt to control it through legislation and violence.

Dionysus, despite his apparently uncontrollable sexuality and many lovers, is one of the few Greek gods to love and respect his wife, something that is probably also meant to emphasise his departure from “proper” masculinity. He found Ariadne, a mortal princess, abandoned by the hero Theseus after she had forsworn her family and her people in order to marry him. Unlike most of the gods in the pantheon, who would have responded to seeing a lone, pretty mortal by raping her, Dionysus rescues her, woos her and makes her his consort. He never abandons, insults or forsakes her and, while he does take other lovers, she seems totally fine with this, clearly being down with her non binary spouse’s casual poly lifestyle.

Viciously defending his own honour and the safety of his followers, Dionysus is a god for the queer, the feminist and particularly those whose gender falls outside of the cisgender binary. As the divine pioneer of weaponising a party to defend your rights, the upcoming Pride season seems like a particularly appropriate time to call on him, so pour him a drink and invite him in.

*though I argue that Dionysus has a non binary transfeminine identity I am using male pronouns because those are the ones the sources texts used for various cultural reasons.