Born Mnēsarétē (meaning “commemorating virtue”) in the Greek city of Thespiae in 371 BC, she spent her childhood and adolescence in Athens where she worked as a hetaira (translated into English as a courtesan or high-status, educated prostitute). Her pallid complexion soon earned her the nickname Phryne (meaning “toad”), and while this may seem an unflattering name for arguably the ancient world’s most beautiful woman, it was commonly given to prostitutes. Plus the Athenians, like the Romans after them, were notoriously mean with names: Plato, for example, meaning “broad”; the philosopher’s real name was Aristocles.

Phryne was damn good at her job. She earned a fortune selling her body and her wit to the highest bidders; so much, in fact, that according to the third century AD writer Athenaeus, she offered to rebuild the walls of the Greek city of Thebes, razed by Alexander the Great in 335 BC. Her only condition was that on the walls it should be inscribed “Destroyed by Alexander the Great; Rebuilt by Phryne the Courtesan”. Regrettably (though unsurprisingly), it doesn’t seem Thebes took her up on the offer. More than just being a ravishing beauty, however, she also had the brains and personality to match.

Athenaeus’s concisely titled “Deipnosophistai” or “Sayings of Philosophers over Dinner” has preserved for us a number of anecdotes showing Phryne razzling and dazzling through her sharp wit and clever wordplay. One one occasion, one of her notoriously stingy Athenian lovers asked her if she was really the model behind Praxiteles’s famous Aphrodite of Knidos statue. Evading his question, she asked him if he was Eros of Pheidias (Pheidias was the name of another sculptor, but it was also a play on the word pheido, which meant “stingy”). Hey, I never said it was funny, just clever…

Her tight lover wasn’t the only man she called a statue. She once found herself in the rather intimate company of the philosopher Xenocrates, but try and she might she failed to seduce him (something that, given her renowned beauty presumably seldom happened). Her sharp retort was to mock him by calling him andriantos: a statue of a man rather than a living, breathing man.

If Phyrne was in fact the woman behind Praxiteles’s Aphrodite then we have a pretty good idea what she looked like. And the fact that not only Athenaeus but also Pausanius (History’s first travel writer and the author of the “Description of Greece”) tells us that she was is pretty strong evidence that when we look at this statue, we’re looking back through time at Phryne herself. But according to Pausanius, Phryne wasn’t just the model behind Praxiteles’s Aphrodite; she was also the renowned artist’s lover.

Phryne certainly knew how to keep her celebrity lover hooked. One day she asked Praxiteles which of his many works was his favourite. As well as a beautiful statue of the God of Love (Eros), the he had recently finished a Satyr statue he was particularly proud of. He told her that he would gift her his favourite work, but wouldn’t tell her which one it was. Cunning as ever, Phryne waited a while before sending one of her slaves running up to Praxiteles to tell him his studio was on fire. Not all works were lost, the slave panted, but if he didn’t come quickly they soon would be.

Making a dash towards his studio, Praxiteles desperately cried out that if his Satyr and Eros had been consumed by the flames all would in fact be lost. But a grinning Phryne intercepted him on his way out the door. There had been no fire, she said, but she had at least tricked him into revealing which works were his favourite. Smugly, she told him that she would take the Eros. Defeated, he obliged. This isn’t the only version however. Athenaeus relays the same story, but tells us that upon giving Phryne the statue, Praxiteles demanded they retire to his bedroom to make love “without an extra charge.”

The indication here is that, rather than being his lover, Phryne was still working in the capacity of a courtesan and Praxiteles was her client. The exceptional nature of her gift, however, led the artist to believe he deserved something extraordinary in return. According to Athenaeus, Phryne hesitated initially—unsurprisingly given the Weinsteinian situation she found herself in. She agreed eventually though, more out of fear for offending and angering Eros than for anything else.

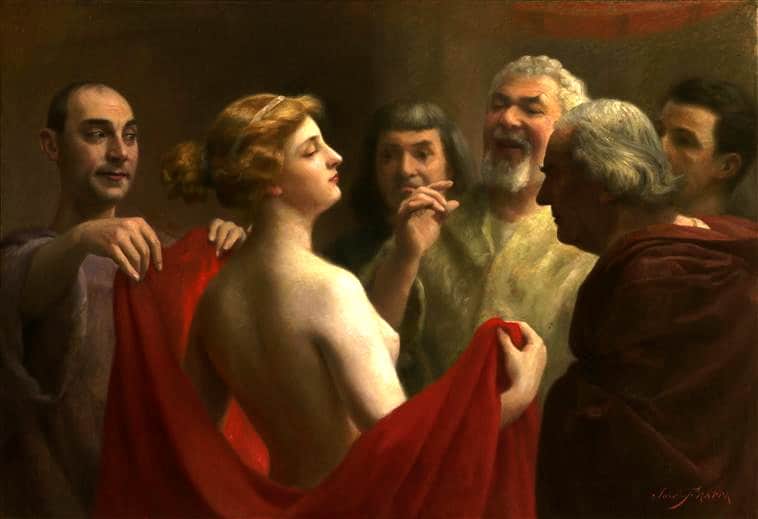

The anecdote of Phryne tricking Praxiteles is a mere footnote to the main event of their relationship: her posing as his model for the famous Aphrodite statue. So what was the story behind this statue? Most of our informatoin comes from the first century AD Roman encyclopaedist Pliny the Elder. Pliny writes that around 330 BC, the people of the Greek island of Kos commissioned Praxiteles to make a statue of the goddess. He accepted, but in the end went above and beyond to sculpt two: one clothed and one naked.

When Praxiteles presented them to the people of Kos they were horrified. Though they may have been statues of the goddess of love and sex, one’s nudity contravened all artistic conventions of the time (while men had been appearing naked in statues for 300 years, female nudity—particularly divine female nudity—was unheard of). Kos’s residents bought the clothed statue. But their neighbours, the people of Knidos, invested in the nude Aphrodite. And what an investment it was.

It grabbed the attention of the king Nicomedes, who promised to cancel Knidos’s vast debts in exchange for the statue. The Knidians refused of course; they loved their statue too much. And to make sure it could be enjoyed from all angles they constructed an open temple to house it that would make it constantly visible for everyone in the vicinity. I use enjoyed hesitantly; several stories go that a young, local nobleman fell madly in love with the statue and at the height of his desires actually hid overnight in the temple so he could spend the night with it.

Come the morning, a curious stain was visible on the statue’s thigh, bearing witness to the young man’s debauched nocturnal… activities. Overcome with shame for what he had done, the young man threw himself off a cliff into the waters below, never to be seen again. His legacy lived on though; the stain still visible years later when the second century AD satirist Lucian visited the temple and left us this story.

Unfortunately, the original masterpiece doesn’t survive. Or it hasn’t been found at least. The last mention of it came from Constantinople in the early Christian period, and in all likelihood it was destroyed in the fire of 476 AD. But many copies survive from the Roman period, giving us a perfect idea of what the original looked like. What makes the Aphrodite so significant is that it was the Greek world’s first full-scale nude statue, depicting the goddess in her naked, natural state; oozing sexuality while simultaneously retaining an aura of modesty.

It’s not just for being the inspiration behind Praxiteles’s Aphrodite that Phryne achieved immortality. Arguably the most famous moment in her long and eventful career was her trial. We don’t know when exactly it happened, nor do we know the charge brought against her. One source suggests impiety (the same charge that got Socrates executed in 399 BC) but another suggests she spoke badly of the Eleusianian Mysteries.

For one of the most important cult rituals of the ancient world, we know remarkably little about the Mysteries—you can see a pattern emerging here!)—only that it was celebrated with a ritual held every year to commemorate the abduction of Persephone, daughter of Demeter, goddess of the corn, by Hades, god of the underworld. When it comes to the details, however, we’re just as much in the dark as Persephone was on her descent into the underworld.

Whatever the charge, it was serious enough to warrant the death penalty. Fortunately for Phryne, one of the most distinguished orators of the time, Hypereides, also happened to be her lover, so that was her defence sorted. Unfortunately for Phryne, the man bringing the charges against her was Anaximenes of Lampsacus: another big name in Athenian oratory and incidentally the inventor of extemporaneous speaking.

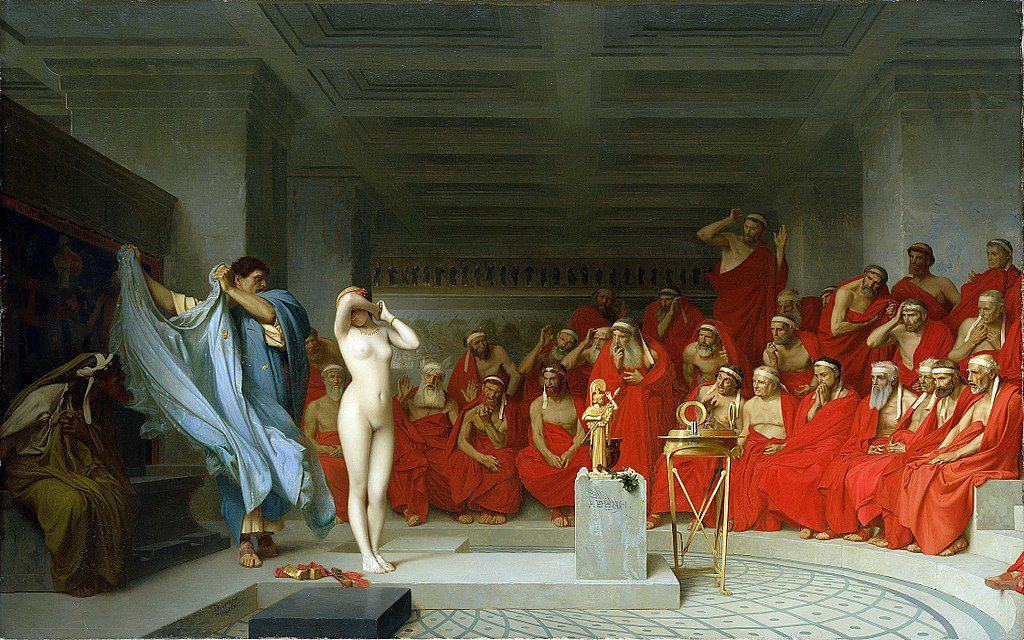

As the trial got underway, it became ever more apparent that Phryne’s defence was wavering and that the judges were likely to return a guilty verdict. This drove her lover and protector Hypereides to extreme measures. Grabbing her robe, he yanked it from her body, bearing her breasts to the judges and leaving her standing completely naked. Her stunning beauty (combined with her abject misery and the possible divine favour granted her by the goddess Aphrodite) moved the judges to reconsider their decision, and she was acquitted.

Many have argued that this story was a later invention, intended to satirise the Athenian legal system and ridicule how sexually corrupt it had become. There are indeed a number of discrepancies between different versions of the trial, one written by a comic playwright Posidippus who makes no mention of the nudity (a detail he was unlikely to omit had it happened, given what he was writing). But whether it is true or not—and I see no reason to doubt the trial actually took place, nudity notwithstanding—should do nothing to detract from Phryne’s remarkable life.

As with so many details of Phryne’s life, we know nothing about her death. Anecdotes about her life diminished as she grew with age and her beauty waned. But those that survive paint the picture (or, perhaps more appropriately, sculpt the statue) of an exceptional, timeless woman, whose wit and liberality wouldn’t look out of place had she lived today.