In the quest for a deity embodying passion, intoxication, and a defiance of societal norms, Dionysus emerges as the divine muse worth pursuing. Revered as the god of the unfamiliar, the Other, and religious ecstasy, Dionysus traverses landscapes with his consort Ariadne, leading an eternal procession of revelry alongside nymphs, satyrs, and mortal women.

Among his devoted followers are the Maenads, women who willingly cast aside familial ties and societal standings to join his ecstatic journey, surrendering to the primal essence ancient Greeks believed all women inherently possessed. Armed with thyrsi – formidable fennel staves – these women reveled in intoxication, embraced sexual assertiveness, and, when stirred, displayed a propensity to tear apart and consume anything in their path, from lions to their own progeny. Failure to honor Dionysus with due worship and respect might beckon his arrival in your town, potentially enticing women to join the ranks of Maenads or, at the extreme, unleashing them upon unsuspecting men.

“Seizing his left arm at the elbow and propping her foot against the unfortunate man’s side, she tore out his shoulder, not by her own strength, but the god gave facility to her hands. Ino began to work on the other side, [1130] tearing his flesh, while Autonoe and the whole crowd of the Bacchae pressed on. All were making noise together, he groaning as much as he had life left in him, while they shouted in victory. One of them bore his arm, another a foot, boot and all. His ribs were stripped bare [1135] from their tearings. The whole band, hands bloodied, were playing a game of catch with Pentheus’ flesh.” Euripides Bacchae

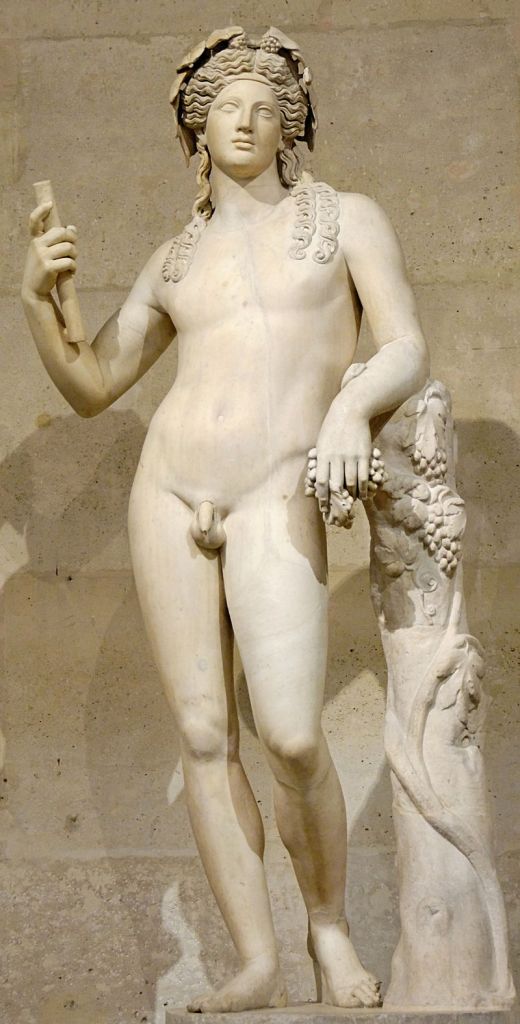

A maenad

Dionysus is a late addition to the pantheon and the myths reflect this. Neither the Greeks nor modern scholars can agree on where he and his cult came from, though the most popular version has him migrating to Greece from central Asia. The bastard son of Zeus and, depending on the source, a selection of women ranging from the mortal princess Semele to Persephone, Queen of the Underworld, all of his origin stories share one feature; that either he or his pregnant mother were killed only for him to regenerate or finish gestating inside the body of a second parent. In all versions of the myth it is Hera, Zeus’ ever-jealous wife, who is responsible for the murder and so Zeus sends him away to Asia or Africa to be raised safely in secret.

This second birth and regeneration made him important in the mystery cults, secretive religions focusing on life after death (Christianity was originally viewed as one and they formed its primary competition until the Christianised Roman Empire eventually banned them). The worship practices of those cults relied on religious ecstasy, the entering of an altered state of consciousness through spiritual transcendence, and generally offered women and other low-status people higher status than the world outside. Dionysus of the cults is usually Dionysus of the underworld, the son of Zeus and his daughter Persephone, or her mother Demeter, goddess of the earth. Known as Zagreus, his death comes in infancy where he is literally dismembered by Hera’s servants, only to regenerate by means of his heart being implanted either in Zeus’ thigh or Princess Semele’s womb. Dionysus here offers his disenfranchised followers — women, the poor and the social outcast — a relief from their misery through pleasure, and the promise of a better afterlife than the uninitiated regardless of social status.

His second birth also ties into his unusual gender identity, not in the historic cult but rather in modern worship and modern gender narratives. Transness is often publicly subjected to narratives of death and rebirth, even while individual trans people frequently reject that characterization of transition Dionysus the twice-born is also the only Greek deity to possess a gender identity that doesn’t align with the one coercively assigned to his body. While Greek myths not infrequently feature physical transformations from one gendered body type to another, and even an intersex god named Hermaphroditus, those figures identified as whatever gender society assigned to the body they were inhabiting at the time.

.

© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.5

His femininity, attached to a body defined as male, is a large part of what made him threatening. Despite ancient Greek women needing to live lives of exemplary sexual self control if they wanted to survive while ancient Greek men happily engaged in orgies and wrote about rape as if it were a casual sport, sexual self control was considered a purely masculine virtue. Intense desire and the inability to control it were the afflictions of women, or particularly effeminate men.

The fact that he sought out women and offered them wine, something their access to was heavily restricted due to the belief that it would make them lose what self control they had, made Dionysus a threat to the fundamental building block of the city state — that a man have legitimate children to replace him. We can still see this fear today in the cis male anxiety around queer and female sexuality, so afraid of losing their sexual dominion over women that they attempt to control it through legislation and violence.

Dionysus, despite his apparently uncontrollable sexuality and many lovers, is one of the few Greek gods to love and respect his wife, something that is probably also meant to emphasise his departure from “proper” masculinity. He found Ariadne, a mortal princess, abandoned by the hero Theseus after she had forsworn her family and her people in order to marry him. Unlike most of the gods in the pantheon, who would have responded to seeing a lone, pretty mortal by raping her, Dionysus rescues her, woos her and makes her his consort. He never abandons, insults or forsakes her and, while he does take other lovers, she seems totally fine with this, clearly being down with her non binary spouse’s casual poly lifestyle.

.

Fiercely guarding both his honor and the well-being of his devoted followers, Dionysus emerges as a deity championing the cause of the queer, the feminist, and those whose gender transcends the confines of the cisgender binary. Serving as the divine trailblazer in harnessing the power of celebration to defend one’s rights, the imminent Pride season beckons as an opportune moment to invoke his presence. So, raise a glass and extend an invitation to the maestro of revelry.

While I posit that Dionysus embodies a non-binary transfeminine identity, it’s crucial to acknowledge the historical use of male pronouns in source texts, influenced by various cultural factors. As we delve into the festivities, let us not only celebrate the liberation he symbolizes but also reflect on the fluidity of identity, embracing the diversity that defines both our mortal world and the divine realms. In doing so, we honor not only the god of parties but also the inherent beauty found in the myriad expressions of gender and identity that thrive under his divine protection.