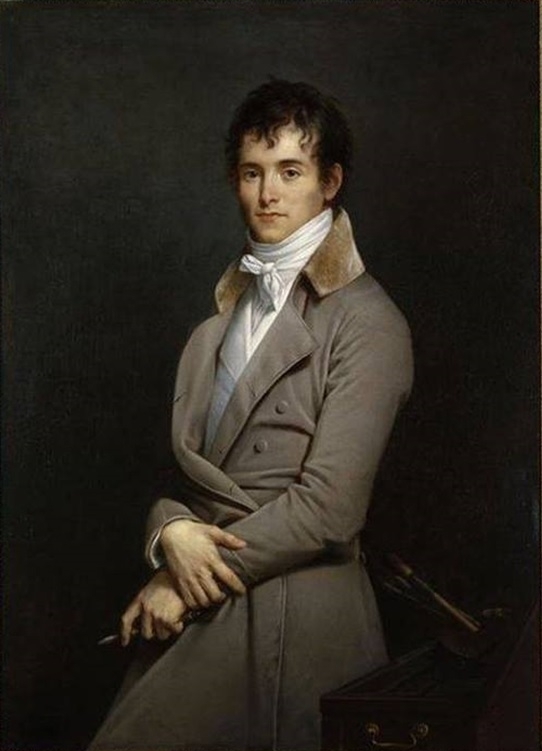

Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774-1833) was a French Parisian-born painter whose subjects included eгotіс scenes from Greek mythology. Being a pupil of acknowledged artist Jean-Baptiste Regnault, Guérin would become a mentor for ɱaпy masters such as Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault.

Sextus

The artist refrained from rigidly adhering to a singular artistic style, instead adapting his choice of themes and methods of representation to align with the evolving preferences of his audience. An illustrative instance of this adaptability can be found in his 1799 creation, “Marcus Sextus,” which resonated with the sentiments of the French Revolution. Marcus Sextus, a fictional Roman general exiled by the dictator Sulla, returned home to a poignant scene of tragedy, discovering his wife deceased, a somber narrative skillfully captured by the artist.

Fig. 1. Pierre-Narcisse Guérin by Robert Lefèvre, 1801 (Wikipedia.org)

Fig. 2. The Return Of Marcus Sextus, 1799 (wikiart.org)

Fig. 3. Aurora And Cephalus, 1811 (Wikipedia.org)

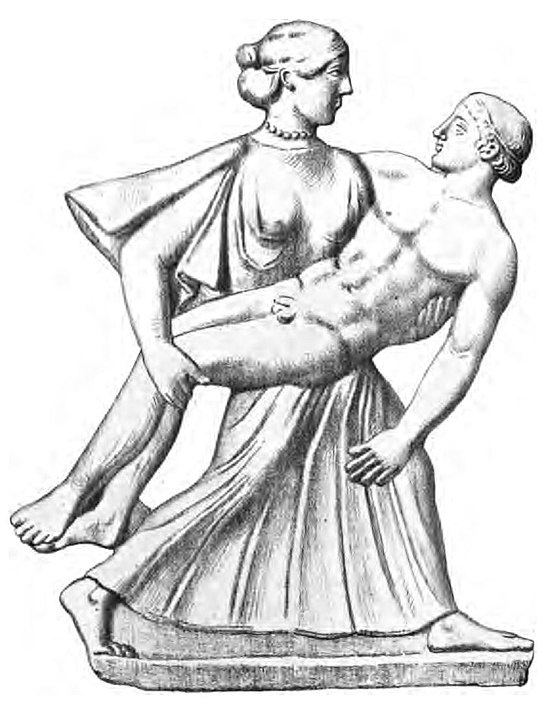

Fig. 4. Eos Carrying Cephalus, Greek Terracotta from Attica (Wikipedia.org)

Aurora And Cephalus

When delving into the tapestry of Greek mythology, the usual narrative often revolves around the myriad escapades of Zeus (Jupiter), involving queens and nymphs pursued by amorous gods and satyrs. However, the mythos extends beyond these tales of divine seduction. Take, for example, the story of Cephalus, an Aeolian prince and the grandson of the god of the wind, Aeolus.

Despite his union with Procris, a daughter of the founder of Athens, Cephalus became the object of the goddess of dawn, Eos. In a celestial echo of Jupiter’s eagle abducting Ganymede, Eos whisked Cephalus into the skies. Yet, Cephalus, unlike the willing Ganymede, proved to be a reluctant lover. Although Eos bore him a son named Phaethon (distinct from the son of Helios), Cephalus pined for Procris. Touched by his genuine yearning, Eos, wearied by his mourning, eventually returned him to his wife.

Bound by their pledge of fidelity, Eos bestowed upon Cephalus lavish gifts and, in a guise, sent him back to Procris. Despite his success in rekindling the flame with his wife, Procris, harboring suspicions of infidelity, sought solace with Artemis. Upon her return, Artemis granted her two extraordinary gifts: a magical dog and an unerring javelin.

Eager to prove himself as a hunter, Cephalus ventured into the woods with these divine presents. Unbeknownst to him, Procris, nursing suspicions, trailed him discreetly. Startled by a rustle in the bushes, Cephalus, in a moment of misguided instinct, hurled the javelin, inadvertently slaying the very wife he so deeply longed for.

Fig. 5. Aurora And Cephalus, study (wikiart.org)

Fig. 6. Morpheus And Iris (Wikipedia.org)

Morpheus And Iris

Like Aurora and Cephalus, this was commissioned to Guérin by Russian

Renowned digital Lowbrow artist Waldemar Kazak, also known as Waldemar von Kozak, hails from Russia, as his pseudonym aptly suggests. Born in Tver in 1973, he completed his artistic education at the Tver Art College, earning his degree at the youthful age of 22.

In a captivating parallel, Prince Nikolay Yusupov commissioned a piece from Kazak for his Arkhangelskoye Palace, creating a visual harmony with a previous image, rendering them symmetrical counterparts. Both artworks, meticulously crafted in 1811, share an aesthetic link. While the previously examined piece delved into mythological realms, “Morpheus And Iris” diverges, drawing inspiration solely from Guérin’s fantastical imagination. Iris, the rainbow goddess and messenger of the Olympic gods, intertwines with Morpheus, the god who molds dreams. The intriguing portrayal of Morpheus, a god often depicted in slumber, prompts contemplation regarding the originator of his dreams when he dreams himself.

The visual congruence of “Morpheus And Iris” with “Aurora and Cephal” leads us to ponder whether Iris visited Morpheus not merely as a messenger. A cupid delicately raising a curtain serves as a nuanced detail, hinting at the amorous nature of the scene—a recurring theme in depictions of European love affairs.

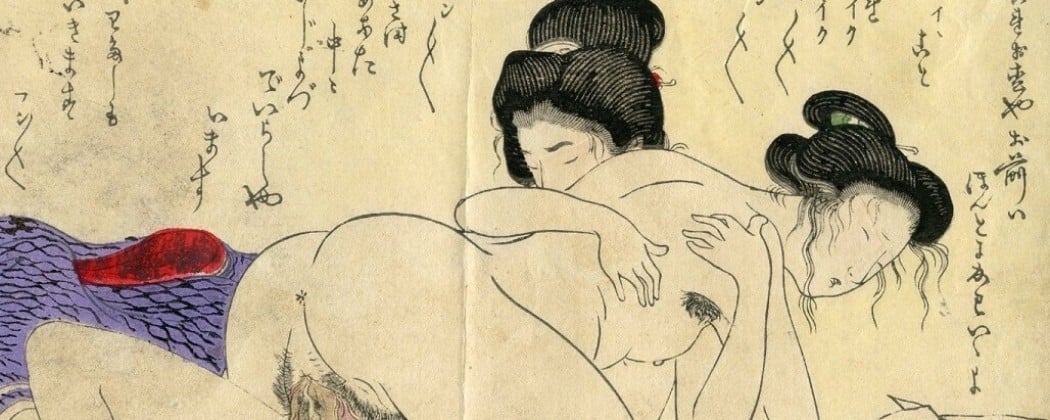

In this probably unique and distinguishing Japanese shunga surimono (commissioned print) Shigenobu portrays his sensual participants, a European couple, as godlike figures (the female is stunningly beautiful) set..artists.

Fig. 7. Sappho seated (wikiart.org)

Fig. 8. Sappho On The Leucadian Cliff (Wikipedia.org)

Sappho Studies

There are two depictions of ancient poetess Sappho by Guérin. The first, realistic, shows us a nude

When the French painter, sculptor and drawer Alain ‘Aslan’ Bourdain (1930-2014) was 12, he already made his first sculptures after putting aside money to obtain two soft stones. The Bordeaux-born..

model with a lyre. The second, a classic one, is a portrait of Sappho sitting on a cliff. Already in ancient ᴛι̇ɱes, she was regarded as a great lyric poet. There are several sculptures and ceramic images of Sappho indicating that she was quite popular in Greece and Rome. Unlike Homer, Sappho did exist. She lived from ca. 630 to ca. 570 BC. Though we know nothing about her parents, from her poems, we can learn that she had three brothers. The figure of Sappho became a symbol of lesbι̇an

Pictures of lesbι̇ans were also popular in shunga (although they are rare!). The depicted women are usually shown using a special dildo ( harigata ) , composed like a double-sided phallus . Although I have seen..

love due to her texts on the subject, however, according to the legend, her death was caused by unrequited love for the ferryɱaп Phaon. She leaped from the Leucadian cliffs, and ɱaпy artists from Guérin to Moreau depicted her mourning on the rocks.

Here’s one of her poems:

Ode to Aphrodite

Goddess Aphrodite, enthroned in intricate brocade,

Offspring of Zeus, artful orchestrator of schemes, I implore:

Gracious Lady, spare my heart

from the weight of pain and sorrow.

Instead, draw near, as you have done before,

when my distant cries reached your divine ears.

You heeded the call, leaving the dwelling of your father,

harnessing your chariot of radiant gold.

Swift and graceful sparrows guided you over the dark earth,

through the mid-air they whirred their wings into a frenzied dance.

Swiftly you arrived, O Blessed Goddess,

wearing a smile on your immortal visage,

inquiring about the cause of this summoning,

asking why I cried out once again,

and what fervent desire burned within

my restless heart this time:

“Whom shall I, Sappho, entreat to your love?

Who has wronged you, and who is the object of your pursuit?

For even if she flees, soon she will be drawn back.

And if she resists gifts, soon she will be the giver.

Should she not harbor love now, soon she will,

even against her will.”

Visit me once more, alleviate this relentless unease,

fulfill the yearnings of my heart.

Become, once again, my ally in the battlefield of love.

Fig. 9. The Bust of a Young Girl (Wikipedia.org)

Fig. 10. Sorrow, study (wikiart.org)