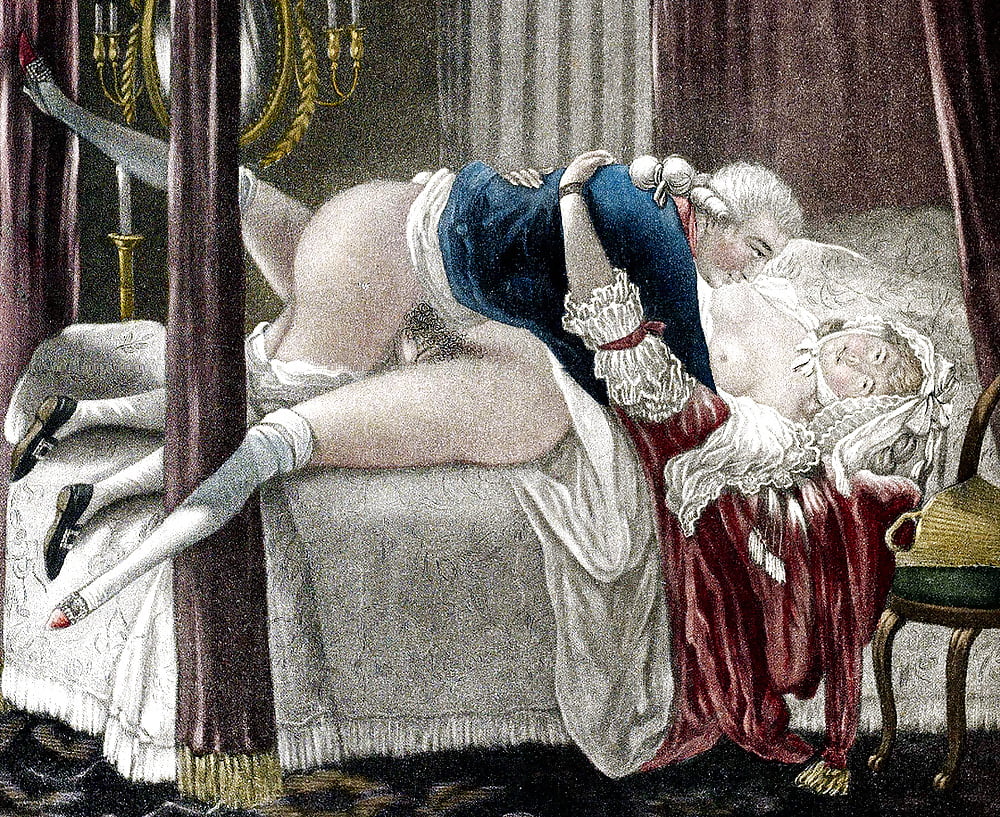

In discussions surrounding sexual, erotic, or nude imagery, there often exists a potential for confusion when determining whether an image falls within the realm of the erotic or crosses over into pornography. This confusion is, in part, rooted in the artist’s intention. “The Erotic harbors aspirations beyond mere desire [and] sexuality. The Erotic tends to be something that engages with morality, psychology, and the boundaries of permissibility,” explains Alyce. “On the other hand, the pornographic body is present purely as a sexual aid – something designed solely to arouse sexual pleasure.”

.

.jpg)

.jpg?mode=max)

Salvador Dalí made bold political statements through Eroticism in his work by exploring homoerotic desire at a time when the Nazis were gaining power and attacking homosexuality as ‘degenerate.’ “The idea of him exploring same-sex desire wasn’t just an exploration of his own self or an homage to what Surrealism was trying to do, but it was a very defiant political move,” says Alyce.

Dorothea Tanning takes yet another perspective in her “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” by exploring the idea of burgeoning womanhood and being on the cusp of transitioning from a girl to a woman. This includes sexual awakening among other bodily and psychological developments. It also taps into the psychology of dreams, which was a recurring theme in many Surrealist works.