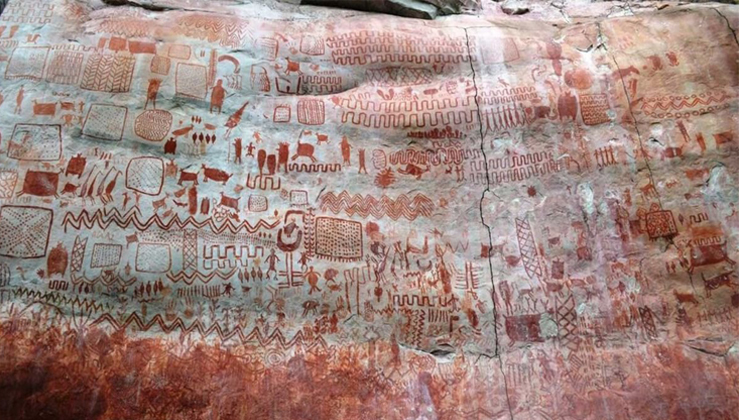

Deep within the dense Amazon rainforest in modern-day Colombia, an 8-mile-long “canvas” filled with ice age drawings of giant sloths, mastodons and other extinct beasts has been discovered. The amazing drawings made with ochre – a red natural clay pigment widely used as paint in the ancient world – are located at in the Colombian Amazon, at a remote site known as Serranía de la Lindosa.

They span nearly 8 miles (13 kilometers) of rock on the hills above three rock shelters. The myriad of detailed illustrations date back to between 11,800 years and 12,600 ago – just as the world was warming up and coming out of the Ice Age. Discovered by British and Colombian archeologists back in 2017, the public is just now getting a first glimpse of this prehistoric site. The stunning example of prehistoric art, which has been dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of the ancients,” promises to reveal important information about prehistoric South Americans.

“These really are incredible images, produced by the earliest people to live in western Amazonia,” study co-researcher Mark Robinson, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, who had a chance to analyze the rock art together with Colombian scientists, said in a statement. To be able to study the drawings of Serranía de la Lindosa, researchers needed to clear their mission with both the Colombian government and the unallied rebel forces in the region. Then they had to walk for 5 hours to reach the site. The scientists were awed by the sheer number of individual paintings which, although yet uncounted, number in the tens of thousands. They depict prehistoric humans among the flora and fauna which once populated the Amazon region. Fish, lizards, and porcupines would be recognizable to the modern viewer, but the drawings also depict extinct prehistoric creatures such as giant sloths, palaeolama or mastodons. Those creatures roamed a savanna and scrub brush landscape which was quite different from the modern rainforest.

The ancient artwork also depicts prehistoric humans who wear masks, hunt – and dance. However, at this point the archeologists examining the paintings can only make guesses as to what certain scenes actually mean. Still, they are certain that the Serranía de la Lindosa paintings will provide a critical insight on prehistoric human behavior and also, human-animal interactions. There is definitely an odd one among the behaviors depicted in the drawings: humans suspended or jumping from wooden towers. The research team believes structures such as these may explain how the ancient artists painted scenes well above a typical human’s height on the cliff wall.

The cliff art gives a snapshot of a world in environmental flux at the end of the last Ice Age. During that time, “the Amazon was still transforming into the tropical forest we recognize today,” Robinson explained. Rising temperatures changed the Amazon from a patchwork landscape of savannas, thorny scrub and forest into today’s leafy tropical rainforest. According to archaeologist and explorer Ella Al-Shamahi who also had a chance to visit the rocks, “One of the most fascinating things was seeing ice age megafauna because that’s a marker of time. I don’t think people realize that the Amazon has shifted in the way it looks. It hasn’t always been this rainforest.”

“The paintings give a vivid and exciting glimpse into the lives of these communities,” Robinson said. “It is unbelievable to us today to think they lived among, and hunted, giant herbivores, some which were the size of a small car.” According to the researchers, many of South America’s large animals went extinct at the end of the last Ice Age, most probably through a combination of human hunting and climate change.

Excavations within the rock shelters revealed that these camps were some of the earliest human-occupied sites in the entire Amazon. Together with the paintings, they offer clues about the diet of these early hunter-gatherers, the researchers said. For example, the bone and plant remains found indicate that their menu included palm and tree fruits, piranhas, snakes, alligators, frogs, rodents such as paca and capybara, and armadillos. The rock shelters were excavated in 2017 and 2018, following the 2016 peace treaty between the Colombian government and FARC, a rebel guerrilla group. Following the peace agreement, researchers initiated a project called LastJourney to find out when people first settled the Amazon, and what impact their farming and hunting had on the biodiversity of the region.

“These rock paintings are spectacular evidence of how humans reconstructed the land, and how they hunted, farmed and fished,” study co-researcher José Iriarte, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter, said in the statement. “It is likely art was a powerful part of culture and a way for people to connect socially.” Due to the pandemic, research on the site is currently at a halt, but the team believes the nearby rainforest hides more prehistoric wonders to be discovered.