Discover the diverse lifestyles of slaves whose destiny was irreversibly changed by the centuries-long institution of Roman slavery.

Roman slavery was crucial for Roman society, and slaves had multiple roles and functions. Even if they were at the bottom of the social ladder, their everyday lives were not homogenous. When we think about Roman slaves we imagine work-worn prisoners and enchained captives, ripped away from their homeland and forced to live submissively under the Romans. But that was not always the case. Slaves who were cherished by their masters had a higher quality of life than some of the free Romans who surrounded them. But who were these individuals? What were their lives like?

Contrasting Roles in Roman Slavery

Roman slaves, servi, were war captives and survivors from conquered tribes. Prisoners and products of piracy, they could be purchased on the market like any other product. Slaves were goods that could be bought, sold, tortured, or killed. Roman law regarded them as res mancipi (Gaius Inst. 1.119–120), they belonged to the category of valuable goods, like land and large animals. In Res Rustica, a book that discusses agriculture in the form of an academic dialogue, Varro defined slaves as instrumentum vocale or “talking tools”.

The Roman custom of mass enslavement came with conquest and the expansion of territory. In the late Roman Republic, continuous wars, foreign and civil, provided a supply of slaves that circulated the markets of the Mediterranean. At that time, women and children were not used as slaves, but after the end of the Republic, the diversity of slaves began to grow. Together with so-called slave-breeding, by the second century, Roman slavery played a much larger role and numbers grew rapidly. For example, in the three wars against Carthage, more than 75,000 captives were imprisoned and sold into Roman slavery.

The enormous influx of slaves from different tribes, cultures, and backgrounds led to tension that resulted in three slave rebellions. The Servile Wars were repressed and they were the only occasions in which major slave revolts shook the institution of Roman slavery. We cannot neglect the numerous, but forever unknown, lionhearted escape attempts that were made by individual slaves, led by their desire for freedom.

Hierarchy Among Roman Slaves

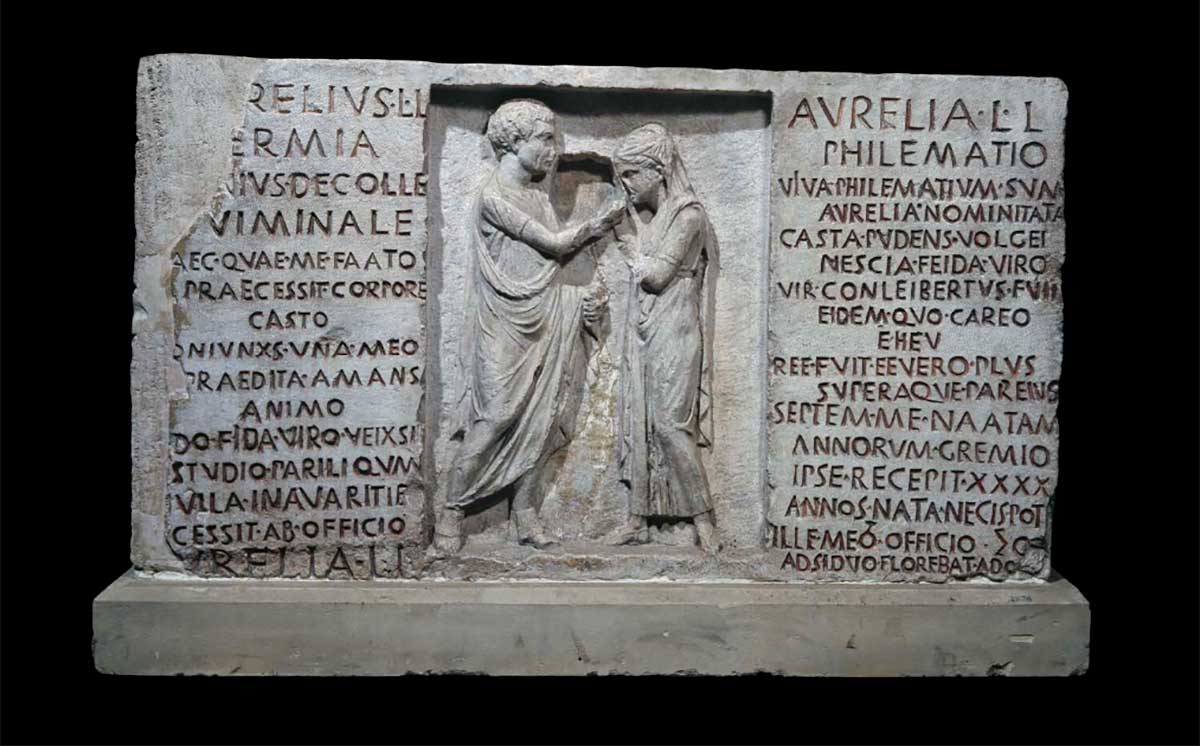

Some slaves, because of their skills, hard work, or good looks, could climb up the hierarchical ladder of slaves in the familia. They could become those who controlled other slaves, or they could be manumitted — freed — quicker. Some could gain true affection or start a relationship with their masters.

Elite households in Rome and the provinces had numerous members, both enslaved and free. Tacitus had 400 slaves in his household at Pedanius. As an urban prefect, this may have been symbolic, but owning a high number of slaves demonstrated wealth and social importance in urban areas (Tac. Ann. 14. 43). A household that kept more than one slave aimed to have slaves of different origins. The goal was to prevent any kind of deal between fellow slaves, which could lead to a riot. A large number of slaves per household led to a division among the slave class. Male slaves who were favored and trusted, named vilici, were given the responsibility to overlook the work of other slaves on the rural estates.

Another important function was held by slave educators. These educators were male and took care of the master’s children from an early age. They would teach various skills and had to be educated themselves. This meant they were sophisticated and knowledgeable, and had a higher rate of gaining freedom.

Another major source of the Roman slave supply was reproduction among the existing slave population. Children of slave women inherited social status from their mothers. These slaves, called vernae, had different treatment from foreign, enslaved captives. They were known by their masters, even cared for. They were privileged, even though they were lawfully unfree. Home-born slaves had easier jobs and spent their lives in the urban domestic spheres. For example, they worked as tailors or food-tasters, while foreign slaves and captives were sold into gladiator schools or were chained while doing physical labor in provincial mines.

Enslaved women in urban areas accompanied their mistresses, bathed them, were their hairdressers or babysitters. In rural areas, they were kitchen maids, wives of vilici, or maidservants. When it comes to the personal lives of female slaves, they were not allowed to marry fellow slaves, or to keep their children.

Even though formal marriage, conubium, was forbidden, illegal unions like marriages were common. Slave children primarily belonged to the master and were every so often his own biological children. These Roman slave children grew up and played with masters legal, free, and favored children. This demonstrates the complicated dynamic of a Roman familia. Women in Roman slavery were frequently separated from their children, who were commonly sold off, or ordered to look after their master’s children, until the care of these children was taken over by slave educators who were male.

Some Roman slaves, male and female, were sold as prostitutes by their masters, who would financially gain from their sexual and physical abuse. It is taken without question that slaves were objects of sexual gratification for people who owned them. To the emperor Marcus Aurelius it was a source of spiritual gratification that he had not taken sexual advantage of two slaves (Meditationes I.I7) when it had clearly been in his power to do so.

Female slaves were also present in Roman religious practices. Firstly, slave women were prohibited to take part in the popular Matralia, a women’s festival held annually on the 11th of June. The cruel exception was that during the ceremony, a slave girl was ritually beaten by and then expelled from the company of the free. A second ritual practice was simply called the “Slave Women’s Festival” (ancillarumferiae), which in historical times was celebrated each year on the 7th of July. The traditional explanation of the festival is to honor a group of slave women who had saved the city from its enemies in the 4th century. The representation of female slaves varied.

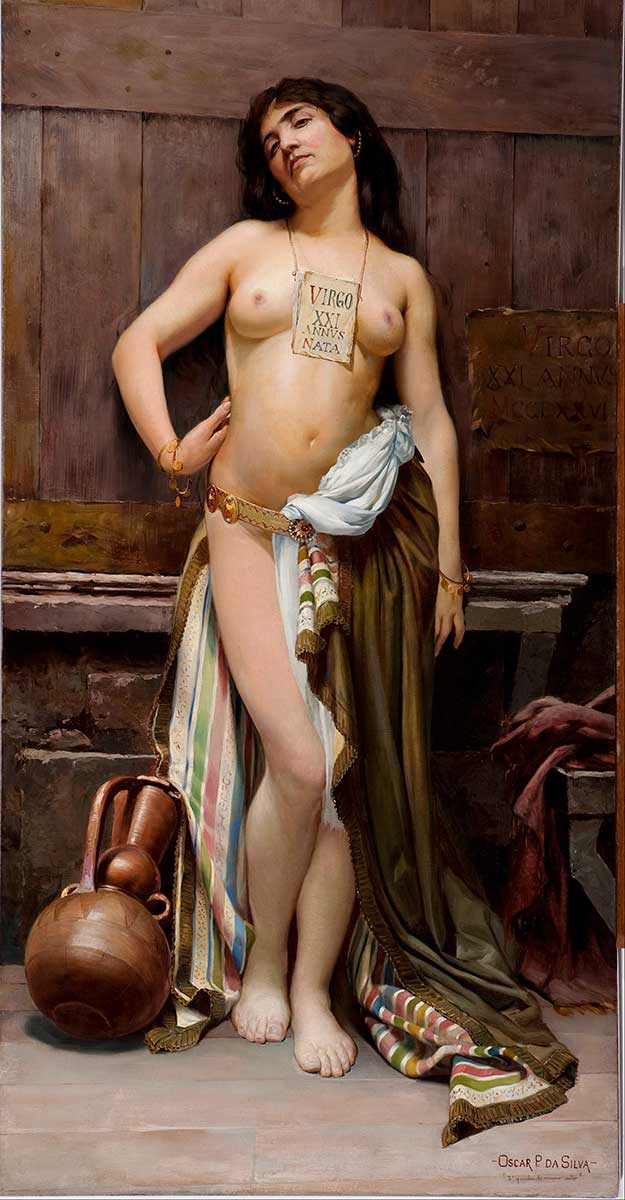

Slave Markets

As history shows us today, slavery itself is a culmination of inequality in human relationships. Slaves were a common sight in Roman market places, standing half-nude with a wooden sign hanging around their necks. Every male, female, or child had a wooden sign that contained all the important information about a certain slave. Name, age, skills, or other specifications were written. When a slave was sold, the law required certain procedures to be followed. One of which was that the seller should declare whether the slave was diseased or defective in any way in case the slave’s capacity to perform was at all diminished. Jurists frequently had to rule and decide on what constituted as a disease or defect because disagreements often arose about the slave performance.

Enslaved family members were sold individually and slave mothers were separated from their children. This action was, besides the tragic circumstances of the slavery itself, extremely psychologically draining. Nowadays, we can only imagine what it was like to be ripped out of a tribe or culture only to be forced to stand in a Roman market, where people bid and bargained over the price of you.

Slave Collars and Shackles

Roman slaves who worked in fields or mines had the toughest and most tiresome lives. They would sleep in barn-like constructions, had little to eat, and wore chains around their feet that not only burdened them, but reminded them of their destiny without freedom. They were consumer goods who worked till death. These slaves had absolutely no chance of gaining freedom, other than escaping. It was instinct that slaves wanted to run away, and it was something masters feared. Those who did run away, not only from tough physical work, but also from the other branches of work, were extremely courageous. If a fleeing slave was spotted, they would have been killed, or returned to their master to be tortured. The best evidence is the famous iron slave collar with a bronze tag attached, found in Italy. On the tag there is an inscription that reads:

“I have run away; hold me. When you have brought me back to my master Zoninus, you will receive a gold coin.”

Tensions and the stress of life in Roman Slavery could lead to many scenarios that ended fatally, for master or slave. The best example is probably the most famous Roman slave today, Spartacus. Like cattle, they often had stamps or tattoos on their forehead that could state their master’s name.

There is no doubt that the Roman Empire ran on slaves. They were a key part of the Roman socio-economic system and a crucial factor in the lives of Roman citizens. The institution of Roman slavery was brutal. Slaves were sold like animals, and physically and sexually violated. They worked in extreme conditions, were mocked, and lived with a constant feeling of inferiority. Today we can only imagine what it was like to be a captive of the Roman army, waiting on a marketplace, to be bought into servitude, probably forever. We can only imagine what it was like to suddenly be deprived of freedom in life, to be taken away from your family, or to observe your loved ones being sold off.

Roman slavery was never officially abolished. As the Empire perished and deteriorated, the slave system weakened and in the Late Antiquity transformed into a new class of labor workers.