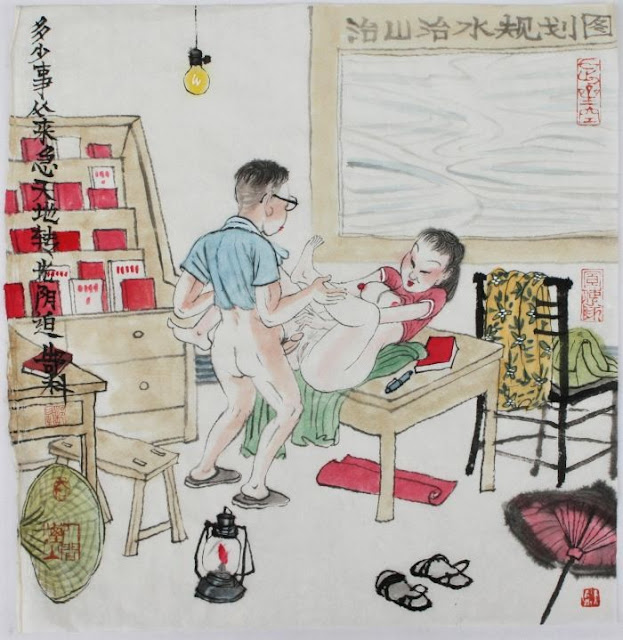

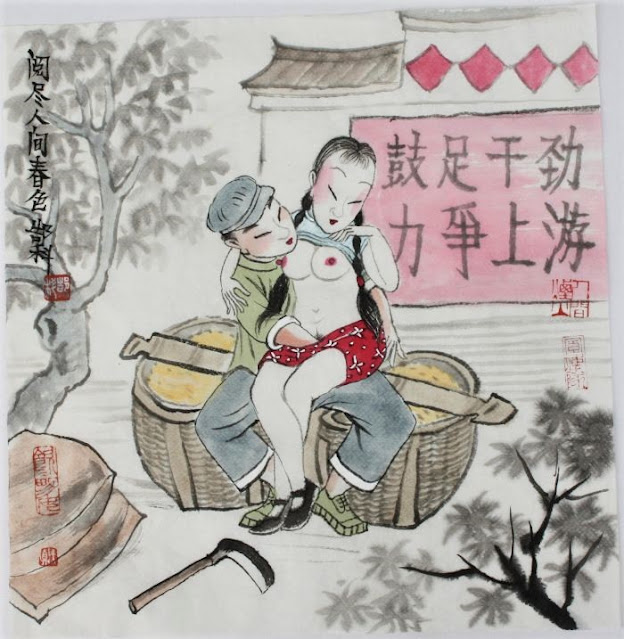

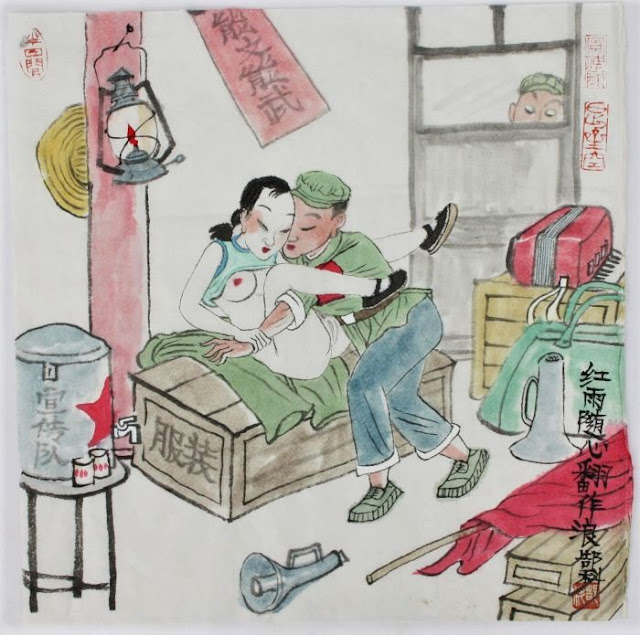

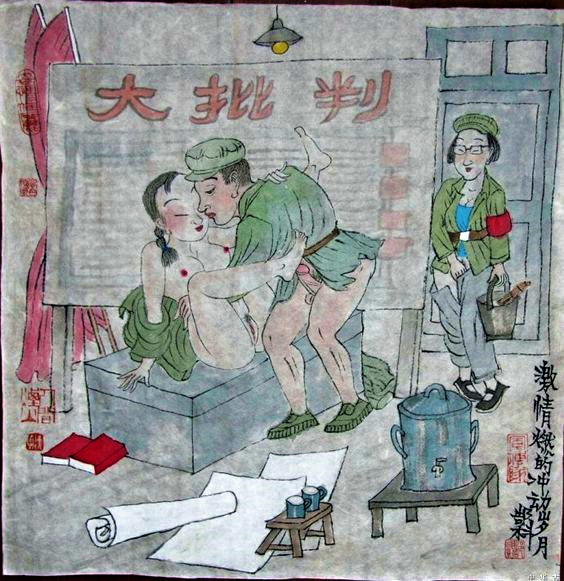

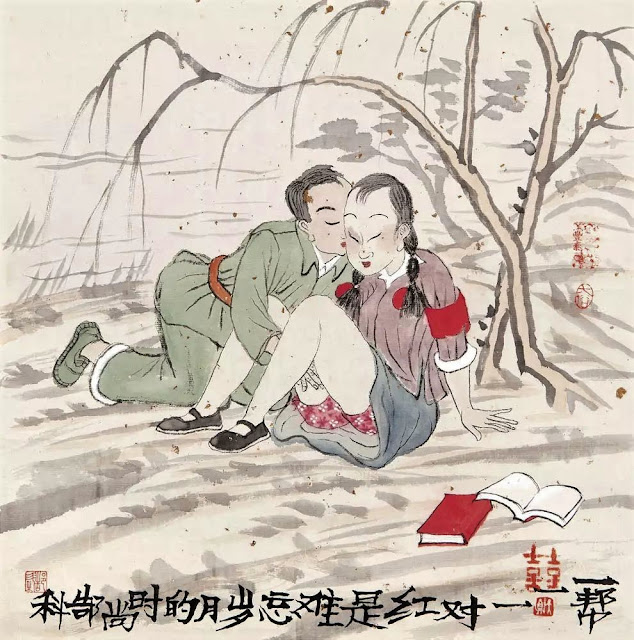

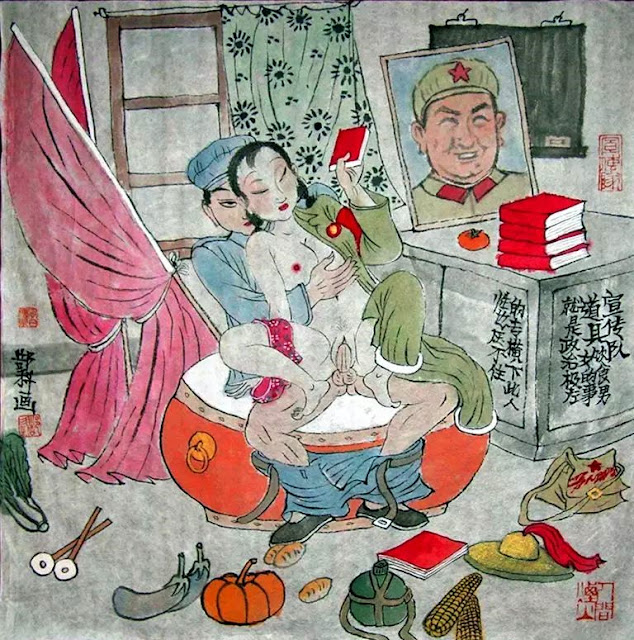

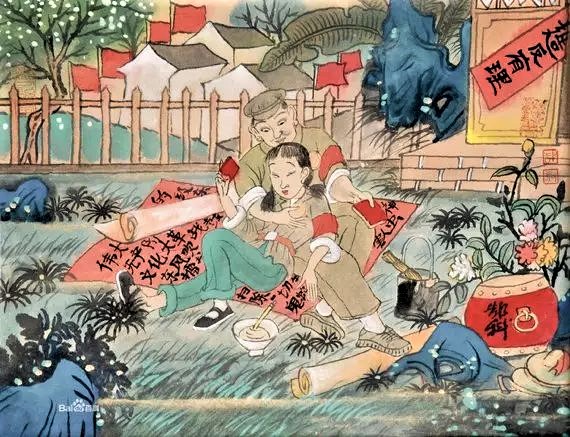

For over a decade since 1966, there has been a struggle for political power in China, known as the “Cultural Revolution,” in which even the masses eagerly participated. The whole country fell into extreme political movements, the food shortage crisis, the country was impoverished, and the people were silenced. In that context, artist Cáo Khoa depicted strong and resilient individuals surviving in the Cultural Revolution through the genre of Xuân Cung Hoạ painting with a rebellious spirit, as a way of critiquing the “Great Criticism.” These artworks introduced the Xuân Cung Hoạ of the Cultural Revolution as a folk painting, while also looking back at a dark period in China, regarding educated youth and artists being sent to the countryside. These works have been exhibited nationwide since 1980. Cáo Khoa has also had solo exhibitions in Seoul (South Korea), Tokyo (Japan), the United States, Canada, and the Central Art Museum in Moscow. His works are widely collected, including by the British Museum.

Artist Cáo Khoa (born in 1956 in Hefei, Anhui Province) was once a Red Guard and educated youth sent to the countryside, giving him profound experience with reform. After the Cultural Revolution, Cáo Khoa graduated from China’s Art Academy in Nanjing, majoring in Chinese painting. He is currently the Deputy Principal of the Kim Lăng Fine Arts Academy and the Director of the Jiangsu Provincial Fine Arts Association. He is also a special artist of the Nanjing Museum and a special calligrapher of the Chinese Painting Institute and the Chinese Calligraphy Research Institute.

“The Cultural Revolution is a rare catastrophe in the history of human civilization. In reality, this movement is not an ideological system, but a struggle for power. As time goes by, the authorities have taken advantage of collective silence to create collective amnesia. The famous writer Ba Jin once proposed the establishment of a Museum of the Cultural Revolution to warn future generations. The renowned writer Thiểm Tây wrote the novel “Giả Bình Ao” based on the context of the Cultural Revolution, with the purpose of not letting future generations forget this destruction of human civilization. I have chosen to record those rebellious individuals, the Red Guards, Worker-Peasant-Soldiers, and Propaganda Teams at that time, in the form of Xuân Cung Hoạ paintings, which can be seen as a museum of customs on paper.”