Almost everyone harbors regrets at some point in their lives. For gifted artists, these regrets can sometimes lead to the destruction of their own creations. Numerous instances exist where society censored works of art, but equally prevalent are situations in which artists themselves become the architects of censorship, either due to changing convictions or concerns about their reputation. The ability of provocative artworks to leave an indelible mark on an artist’s career amid the apprehensive and repressive atmosphere of conventional communities is a subject of intrigue.

Matthew William Peters (1742-1814), an English portrait and genre painter, stands as a fascinating example. Renowned for his audacious depictions of courtesans, Peters defied societal norms with sensual portraits. Remarkably, these provocative works did not hinder his subsequent transition to a clergyman, and, ironically, his religious compositions emerged as his most celebrated masterpieces. Peters’ journey from controversial portrayals to ecclesiastical acclaim serves as a compelling narrative within the complex and often censorious milieu of artistic expression.

Fig. 1. The Sisters, са. 1790s (gallery.са)

Fig. 2. Sleeping Girl, attrib. to Peters (Artory on Twitter)

The іпfɩᴜeпсe of Society

Peters was born into the family of a civil engineer in Freshwater, Isle of Wight. During his youth, the family relocated from England to Dublin when Peters’ elder relative was invited to enhance loughs and rivers for navigation. Under the tutelage of Robert West, the founder of the local drawing school in Dublin, Peters received his education. Demonstrating remarkable talent during his studies, Peters garnered the attention of the Dublin Society, which sponsored his journey to London. There, he underwent training under the English portrait painter Thomas Hudson and earned a premium from the Society of Arts.

Buoyed by his training in London, Peters continued to expand his artistic horizons. The Dublin Society further supported his artistic development by funding his travels to Italy, where he immersed himself in art studies from 1761 to 1765. His time in Italy culminated in his membership in the Accademia del Disegno in Florence. Returning to England, Peters showcased his artistic prowess by exhibiting works at both the Society of Artists and the Royal Academy. In recognition of his contributions to the art world, Peters was honored with election as an academician in 1777.

Fig. 3. Antony and Cleopatra, act 1, scene 2, print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 4. Portrait of a lady as a bacchante, attrib. to Peters (artnet.com)

Fig. 5. Portrait of Miss Morᴛι̇ɱer as Hebe (artnet.com)

Freemason and Clergyɱaп

As early as the 1760s, the artist found recognition within society by becoming a freemason, a testament to the value placed on his artistic talent. Assuming the role of the grand portrait painter for the Freemasons, he showcased portraits of notable figures such as the Duke of Manchester and Lord Petre, who served as Grand Master, at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1785. Concurrently, the artist took on the responsibility of chaplain at the Royal Academy, dedicating four years to this role from 1784 to 1788. Interestingly, this position gradually eclipsed his academic aspirations.

In his own words, Peters explained his decision to resign from the Royal Academy, stating that he aimed to “relinquish his art as a profession and take up a clerical career.” During the peak years of his academic and clerical pursuits, Peters received two livings – Scalford in Leicestershire and Knipton. In 1795, he added the title of prebendary of Lincoln Cathedral to his achievements, securing an additional living at Eaton. Embracing his role as a clergyman, Peters shifted his focus predominantly to religious works. Among his notable creations during this period are a ten-by-five-foot Annunciation for Lincoln Cathedral and “The Resurrection of a Pious Family.”

Fig. 6. Young Lady In Bed (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 7. Sleeping Woɱaп (wikimedia.org)

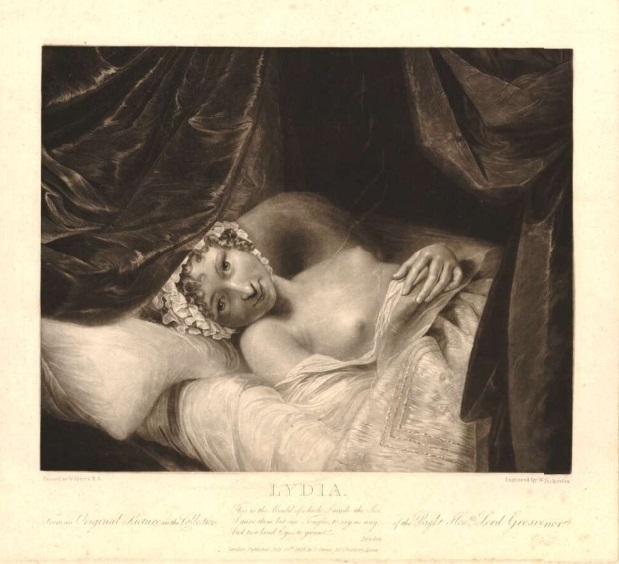

Sylvia, Lydia and Others

Comparing portraits of courtesans Sylvia, Lydia, Belinda, to other depictions of females with bare breasts

Fig. 8. Country Girl, print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 9. Belinda, print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 10. Lydia (artnet.com)

Fig. 11. Lydia (Tate on Twitter)

Fig. 12. Lydia. Print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 13. Sylvia, 1778 (Wikimedia.org)

Fig. 14. Sylvia, print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)

Fig. 15. Print made after Peters (britishmuseum.org)