Artemis and Apollo, the renowned twin siblings of ancient Greek mythology, had a rather tumultuous beginning, marked by the complex circumstances surrounding their birth. Their mother was none other than Leto, a Titaness, but her union with Zeus, known for his wandering eye, sparked considerable trouble.

In an era devoid of contraceptives, Leto found herself pregnant by Zeus. Unsurprisingly, Hera, Zeus’s wife, erupted in fury. Part of her anger stemmed from a prophecy predicting that Leto would give birth not only to a daughter but also to an exceptionally gifted son. In contrast, Hera had given birth to Ares, the god of war, who, while powerful, did not possess the same allure as the gifted artisan god, Hephaestus.

Hera relentlessly pursued Leto, denying her a moment’s peace to find a suitable place for giving birth. Forbidden from resting on any safe land, Leto was forced to seek refuge on the desolate floating island of Delos. Hera, in her relentless pursuit, even impeded Leto’s quest for assistance from Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth. Without Eileithyia’s aid, Leto faced an insurmountable obstacle in delivering her children.

In a twist of fate, Zeus and a few compassionate goddesses managed to appease Hera with a clever bribe, offering her a necklace as a peace offering. This gesture persuaded Hera to relent, allowing Eileithyia to assist Leto in the birthing process. Thus, Artemis and Apollo came into the world, demonstrating that even gods could be swayed by strategic bribes when necessary.

The artwork “Leto Admiring Artemis and Apollo,” created by Latona in 1870, captures Artemis’s elder sister with her hands clasped, standing atop her younger brother. Meanwhile, Leto gazes affectionately at her two children. It’s remarkable how, even as a small child, Artemis assumed the role of a midwife for her mother, showcasing her versatility. This artwork is currently housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Of course, various versions of the birth story of Artemis and Apollo exist. Originally, Artemis, like Hera and Athena, had roots as an ancient goddess before being reimagined as a child of Zeus. Hence, the details of where and how Artemis was born vary in different traditions. Homer only mentions Apollo as the son of Leto and Zeus, omitting Artemis. On the other hand, Hyginus, Pindar, Theogonis, and Apollodorus state that Leto gave birth to both siblings. Some sources claim that Apollo was born in Lycia, while others suggest that Artemis was born on an island called Ortygia before helping her mother cross the sea to Delos to give birth to her younger brother.

To avoid confusion, following the most common version, Artemis and Apollo are said to have been born on Delos.

As for Artemis: Does she have an interest in women or men?

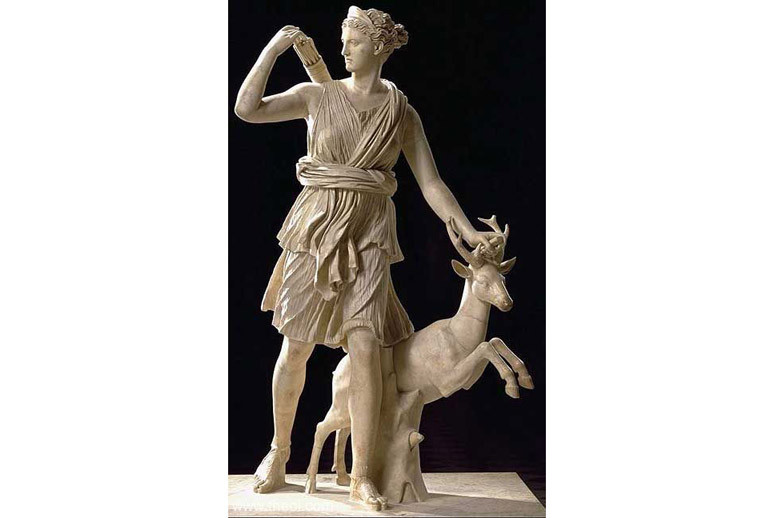

Artemis is traditionally portrayed as a virgin goddess in Greek mythology. She is often referred to as the “Virgin Goddess of the Hunt” and is associated with purity and chastity. In most mythological accounts, Artemis is not depicted as engaging in romantic or sexual relationships with either women or men. Her focus is primarily on hunting, wilderness, and her role as a protector of young girls. However, interpretations of mythology can vary, and modern retellings or adaptations may explore different aspects of her character.

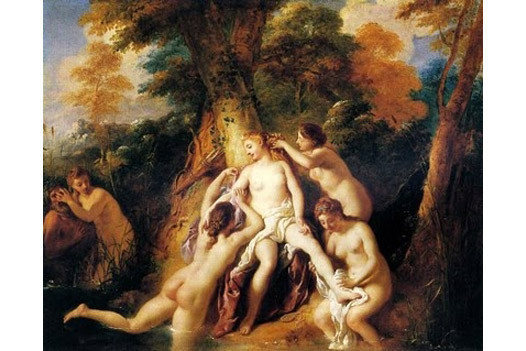

The artwork “Diana and the Nymphs” painted in 1651 by Adriaen van de Velde offers a unique perspective on Artemis (Diana in Roman mythology) not bathing in a river but within a cave. Inside the cave, a statue of her brother Apollo (playing a musical instrument, likely a lyre) and Cupid is prominently displayed. A hunting dog rests on a red cloth, while another stands nearby. Some nymphs, following tradition, attend to Artemis’s hair and bathing, while others engage in conversation with each other. Some carry the spoils of the hunt as offerings.

This painting exudes a more somber and mysterious atmosphere compared to other idyllic bathing scenes. The cave setting adds an element of seclusion and intimacy, perhaps suggesting a ritualistic or sacred aspect to the scene. Adriaen van de Velde skillfully captures the convergence of mythological elements and daily life, creating a captivating tableau that invites viewers to explore the nuanced narrative within the artwork.

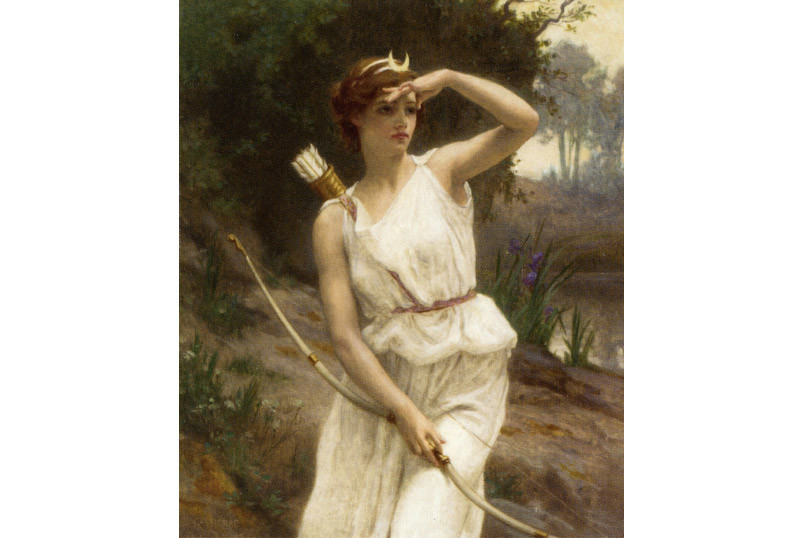

In Barthélemy Gagnière’s artwork, “Diana and the Nymphs,” the depicted scene unfolds as Artemis (Diana) returns from hunting, fatigued and seeking respite. Overcome by weariness, she gracefully reclines to rest. By her side, one of her attendant nymphs is portrayed peacefully sleeping, embodying the tranquility of the moment. Meanwhile, two other nymphs engage in conversation in the background, adding a layer of camaraderie to the scene.

Despite the serene atmosphere, Artemis maintains her warrior demeanor, her hand firmly clutching her bow and arrows. This portrayal captures a poignant moment of tranquility and intimacy within the context of Artemis’s hunting activities. Gagnière skillfully combines the ethereal beauty of the nymphs with the enduring strength and resilience embodied by Artemis, creating a harmonious composition that invites viewers to reflect on the goddess’s multifaceted nature and the balance between strength and repose.

Certainly, associating Artemis with romantic or sexual interests should be approached cautiously, considering the specific myths and artistic interpretations. While some artistic depictions may suggest such interpretations, it’s essential to recognize the complexity and openness to various interpretations within Greek mythology.

In the myth of “Diana and Callisto,” as you described, Callisto is indeed a favorite of Artemis (Diana). However, the myth also involves Zeus disguising himself as Artemis to seduce Callisto, ultimately resulting in Callisto’s pregnancy. When this deceit was discovered, Artemis, often depicted as a protector of chastity, understandably felt angered. The story raises questions about consent, deceit, and the consequences of actions.

As you mentioned, the myth can be quite intriguing and multifaceted, with different elements and moral lessons. It’s always fascinating to explore these myths and their artistic interpretations while keeping in mind the complexities and nuances of Greek mythology.