Discovering a treasure that has lain hidden for countless years is the stuff of archaeological dreams. Today, I’ll regale you with the incredible tale of the recently unearthed golden axe—an artifact that had slumbered for millennia, now brought to light from the depths of history. Join me on this exploration of the captivating history behind this ancient item and the profound implications it carries for our understanding of the past.

In our modern coffee culture, the vocabulary surrounding this beloved beverage has become remarkably sophisticated. Would you prefer a cappuccino, an espresso, a skinny latte, or perhaps an iced caramel macchiato?

Just as our language has evolved, the ancient Greeks demonstrated sophistication in their discourse on love, recognizing six distinct varieties. They would have found our current practice of using a single word to convey both the intimate sentiment whispered over a candlelit dinner and the casual sign-off in an email—saying “I love you” in both instances—quite surprising and perhaps crude.

So, what were these six loves known to the Greeks, and how can they inspire us to move beyond our contemporary fixation on romantic love, where ninety-four percent of young people aspire to find a singular soulmate to fulfill all their emotional needs, often with elusive success?

Let’s delve into Eros, the first of the six loves, representing sexual passion.

The initial facet of love in ancient Greek philosophy was Eros, named after the Greek god of fertility, embodying the concept of sexual passion and desire. However, the Greeks did not consistently view this as a positive force, as we often do today. In fact, Eros was perceived as a perilous, fiery, and irrational form of love that had the potential to seize control of an individual—a sentiment shared by many subsequent spiritual thinkers, including the Christian writer C.S. Lewis. Rather than a benign force, the Greeks regarded Eros with a sense of danger, acknowledging its capacity to grip and dominate those it touched.

Eros, for the Greeks, entailed a loss of control that instilled fear. This paradoxical notion seems peculiar, given that many people today actively seek the thrill of losing control in a relationship. After all, don’t we all yearn to fall “madly” in love?

Moving on to the second category of love, Philia, or deep friendship, held greater value for the Greeks than the primal sexuality embodied by Eros. Philia referred to the profound camaraderie that developed between brothers in arms, individuals who had fought side by side on the battlefield. It encompassed demonstrating loyalty to friends, making sacrifices for them, and sharing one’s emotions with them. (Another variant of Philia, sometimes referred to as Storge, encapsulated the love between parents and their children.)

Reflecting on how much of this camaraderie or Philia we have in our lives is a crucial question, especially in an age where we strive to accumulate “friends” on Facebook or “followers” on Twitter—achievements that would have scarcely impressed the Greeks.

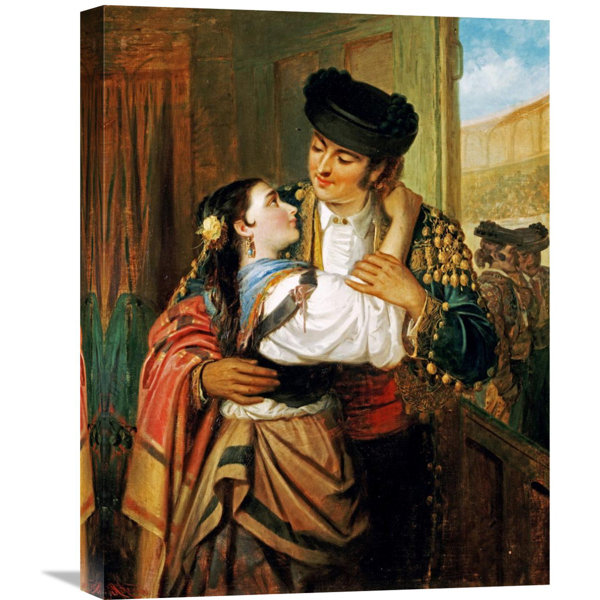

Next in the spectrum is Ludus, representing playful love in Greek philosophy. Ludus encapsulated the affection between children or young lovers. We’ve all experienced a taste of it in the early stages of a relationship through flirting and teasing. However, Ludus is also lived out in our interactions when we gather in a bar, bantering and laughing with friends, or when we hit the dance floor to revel in the joy of movement.

Engaging in dance with strangers may be the epitome of ludic activity—an almost playful substitute for intimacy itself. While social norms might cast a disapproving eye on this kind of adult frivolity, injecting a bit more ludus into our lives could be just what we need to add a dash of excitement to our love lives.

Moving on to the fourth love, and arguably the most radical, is Agape, or selfless love. This was a love extended to all people, whether they were family members or distant strangers. Agape was later translated into Latin as caritas, which is the origin of our word “charity.”

C.S. Lewis referred to it as “gift love,” the highest form of Christian love. However, it also appears in other religious traditions, such as the concept of mettā or “universal loving kindness” in Theravāda Buddhism.

There is mounting evidence that agape, the selfless and universal love for others, is experiencing a perilous decline in many countries. Empathy levels in the U.S. have sharply decreased over the past forty years, with the steepest fall occurring in the last decade. There is an urgent need for us to rekindle our capacity to genuinely care about strangers.

Prаgmа, or longѕtаndіng loʋe

The underlying idea is that if you possess a healthy self-esteem and feel secure within yourself, you’ll have an abundance of love to share with others. This concept is reflected in the Buddhist-inspired idea of “self-compassion.” In essence, as Aristotle eloquently put it, “All friendly feelings for others are an extension of a man’s feelings for himself.”

The ancient Greeks recognized diverse forms of love in relationships with a wide array of people—friends, family, spouses, strangers, and even oneself. This stands in contrast to our common focus on a single romantic relationship in which we hope to find all the different loves wrapped up in one person or soulmate.

The message from the Greeks is to nurture the various types of love and tap into its many sources. Rather than solely seeking eros, cultivate philia by spending more time with old friends or develop ludus by dancing the night away.

Furthermore, we should relinquish our obsession with perfection. Partners shouldn’t be expected to embody all the varieties of love all the time, as this expectation may lead to discarding a partner who fails to live up to those desires. Recognize that a relationship may start with plenty of eros and ludus and then evolve towards embodying more pragma or agape.

The diverse Greek system of love can also offer solace. By mapping out the extent to which all six loves are present in your life, you might discover you have a lot more love than you had ever imagined—even if you feel an absence of a physical lover.