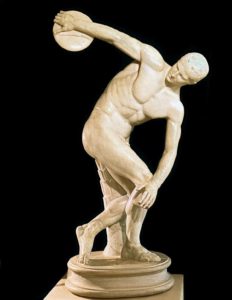

The enigma of ancient sculptures often eludes our perception. The male nude, a staple of Greek statuary for the past 2,500 years, has become so ingrained in our expectations of ancient art that its intricacies often go unnoticed. It’s as if we’ve grown overly accustomed to its portrayal of muscles, at times bordering on the mundane, perhaps reminiscent of the withdrawing room in a 1890s aesthete’s abode, a 1970s gay sauna, or the rear yard of a modern garden center adorned with blue-glazed planters and bird baths.

While the Uffizi in Florence was once renowned for its collection of classical sculptures, one might question who now lingers to admire them as they rush past towards the allure of Botticellis? If the crowds surrounding Hieronymus Bosch’s works in the Prado become overwhelming, one can seek solace in the tucked-away corner where the splendid San Ildefonso statue group resides, offering a sanctuary of peace and quiet. Even when antique statuary competes not with modern painting but with artifacts from more exotic cultures, it struggles to divert attention. Navigating the Egyptian sculpture rooms of the British Museum may prove impossible, yet I often find myself alone with the sculptures that once adorned the mausoleum of Mausolus of Halicarnassus.

Over the past two centuries, ancient statues have experienced a precipitous decline in cultural esteem, a fate arguably more disheartening than that of tapestries and reliquaries, which simply go unnoticed. Ancient statues, on the other hand, are both looked at and unseen, like the taste of water, elevator music, or the scent of air—integral yet overlooked elements of the landscape, akin to lithic wallpaper or garden furniture in the key of C major. It’s as if, by 300 BC, every artistic feat in sculpting the human form had been accomplished.

However, there are moments when the peculiarity of Greek bodies resurfaces in our consciousness. Take, for instance, the opening ceremony of the Athens Olympics in 2004, where real-life models donned peculiar high-waisted, small-willed nude sculpture trousers over clay-grey Lycra shorts, starkly emphasizing the idiosyncrasies of ancient statues. Or the statue of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V of Spain in the Prado, trampling on the demon of Religious War—usually depicted in full armor but arranged to showcase the emperor in the altogether, revealing an imperial torso worthy of gracing the cover of Men’s Health magazine.

Lastly, the Riace bronzes, salvaged from the sea off the toe of Italy in 1972, stand as rare examples of original classical free-standing sculptures, eliciting gasps of wonder and astonishment. These bronzes, originating so close to the source of standard models yet unlike anything seen before, manage to break free from the indifferent gaze we cast upon timeless classics. Perhaps it’s the intricacies—the teeth, eyelashes, and eyeballs—that compel us to look again, if only to ensure they aren’t looking back when we turn away, or maybe it’s the mystery surrounding their origin and creators.

The Greek nude, a subject that remains complex and enigmatic despite years of study, involves more than just nudity in practice, Greek homosexuality, passion for athletics and the gymnasium (“place of undress”), and likely, war. It delves into morality, virtue, and metaphysics. One certainty is that Greek nudity is not merely a result of a lack of self-consciousness or a desire to walk around as nature intended.

The Greeks themselves recognized the peculiarity of their nudity and pondered its origins. One theory posits that an early Olympic competitor, intentionally or accidentally, lost his loincloth and went on to win the 200m sprint, possibly due to some aerodynamic advantage. To keep up, other competitors mimicked him. More likely, it is linked to primitive rituals of “stripping off” one’s childhood cloak and “running out” into the ranks of citizens at the age of 20—a practice continuing in Sparta and Crete during the historical period.

In Athens, as the city sizzled on Athena’s birthday during the hottest time of the year, a tradition unfolded with each graduating class of ephebes streaking from the altar of Love in the gymnasium known as “the Academy” to the Acropolis, brandishing torches. The stragglers and less athletically inclined endured slaps from the spectators as they gasped and panted their way through the main city gate. Nudity, in this context, became a form of ceremonial attire—an idea accentuated by the evident effort spent in oiling oneself up and scraping oneself down. The premier body condiment was the olive oil derived from the sacred olive trees gifted to Athens by Athena, often awarded as prizes in the festivities accompanying her birthday. The resulting salty concoction, known as “boy goop” or paidikos gloios, was sometimes collected and employed to remedy ailments and signs of aging.

However, the gymnasium, criticized by both Plato and the Romans for allegedly fostering Greek homosexuality, appeared to be the primary stage for much of the action. This encompassed not only glances, expressions of affection, and love affairs but also the act of homosexuality itself—mainly a form of frottage in a standing position, referred to as diamerion or “between the thighs.” A chemical analysis of ancient “boy goop” would likely reveal traces of sperm, almost as frequently as swabs of modern computer trackpads. Additionally, the gymnasium serves as the backdrop for a distinctive scene depicted on a vase in the British Museum. In this portrayal, a handsome ephebe climbs onto the erect penis of another ephebe seated on a chair, while a trainer (perhaps) and a woman wait outside. Sir John Beazley, a pioneering scholar in the study of Greek vase-painting, whimsically described it as “Life in the Socratic Circle,” with a hint of humor.

The exhibition doesn’t solely focus on grandiose nudes; it also unveils captivating sculptures like the Marble statue of a naked Aphrodite crouching at her bath, affectionately known as Lely’s Venus—a Roman replica of a Greek original dating back to AD 2. Beyond the monumental figures, the collection features exquisite billowy draperies that accentuate more feminine silhouettes. Particularly mesmerizing is the powerful, fluttering figure of winged Iris, the rainbow messenger of the gods from the west pediment of the Parthenon. Equally compelling is an Amazon sculpture from the Capitoline Museums in Rome, caught in a moment of disbelief as she examines her wounds. The exhibition delves into a rich array of representations, from corpulence to infancy and old age.

Among the intriguing highlights are some of the earliest depictions of black Africans in Western art, showcasing the evolving diversity in artistic expression. A delightful mirror case from Corinth captures a whimsical scene with a benign-looking goat-headed Pan playing knucklebones with a curvaceous Aphrodite. Almost overlooked is a tiny matchstick geometric bronze portraying a man taking his own life, possibly depicting Ajax, the renowned figure in mythology. This discovery could mark one of the earliest depictions of mythological scenes ever unearthed—a testament to the richness and historical significance of the exhibition.

In the final room, the focus returns to male nudes, presenting a captivating juxtaposition of two masterpieces. The first is the Belvedere Torso, a classical marvel renowned for its tension and realism, famously serving as inspiration for Michelangelo. Alongside it stands a reclining figure from the east pediment of the Parthenon, often identified as a young Dionysus but more likely a representation of the constellation Orion reclining along the ridge of Mount Hymettus on the morning of Athena’s birth. This scene serves as an allegory of time, echoing the west pediment with its depiction of rivers and rainbows, which symbolize space.

Upon initially learning about this exhibition, I harbored doubts. While there are some remarkable loans from overseas—a multi-veiled bronze dancer from New York, a life-sized bronze athlete unearthed only in the 1990s in Croatia, and a reclining Hermaphroditus from the Borghese—the undeniable stars of the show are the museum’s own masterpieces, particularly the Parthenon sculptures, many of which I have encountered numerous times before. However, whether it be the strikingly modern space, the dramatic and revealing lighting, or simply the novel juxtapositions, it felt akin to witnessing these artworks for the very first time. This, in itself, stands as quite a remarkable achievement.